News

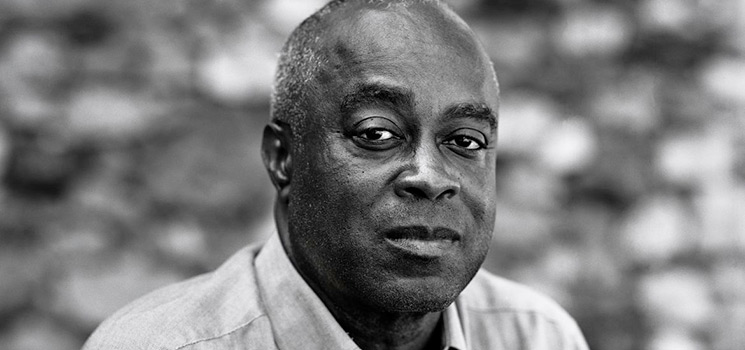

Looking back on the L.A. Rebellion with Charles Burnett

By Noela Hueso

When UCLA alumnus Charles Burnett (B.A. '69, M.F.A. '77) received an honorary Governors Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2017, it was in recognition of his work as an independent filmmaker who has excelled in portraying the African American experience. In his acceptance speech, he was quick to praise his alma mater.

"UCLA was a special place," he said, "because [the instructors] made you create; [they] gave you a camera and said, 'Go out and make a film, and don't come back with something we've seen [before].'"

That filmmaking philosophy propelled Burnett and his fellow students to experiment and try new things. In making his graduate thesis film, Killer of Sheep, he went into the Watts neighborhood in which he was raised, to depict, in a series of vignettes, the lives of urban African Americans in an objective way. Influenced by the neo-realism style of filmmaking, he made a conscious decision to not "impose" his values on his subjects.

Burnett’s Killer of Sheep remains to this day a vital product of what came to be known as the L.A. Rebellion, a group of UCLA student filmmakers, including Julie Dash (Daughters of the Dust), Haile Gerima (Harvest: 3,000 Years) and Ben Caldwell (Medea), who were concerned with the portrayal of African Americans on screen and who saw film as a means for social change. Film scholar Clyde Taylor coined the name L.A. Rebellion.

In the late 1960s, in the aftermath of the Watts Uprising and against the backdrop of the continuing Civil Rights Movement and the escalating Vietnam War, this group of African and African American students entered the theater arts department (now the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television), as part of an Ethno-Communications initiative designed to be responsive to communities of color (also including Asian, Chicano and Native American communities).

In addition to feature films, Burnett's career after graduation included the making of documentaries, shorts and TV projects such as Selma, Lord, Selma (1999) and Nightjohn (1996). His third feature film, 1990’s To Sleep with Anger, won four Independent Spirit Awards and was inducted to the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress.

Still working at 75, Burnett is gearing up to direct a biopic for Amazon about Robert Smalls, a former slave who freed himself, his crew and his family during the Civil War after commandeering a Confederate transport ship and turning it over to the Union navy in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina.

Burnett recently took some time to reflect on his time at UCLA and his career thus far.

How did the L.A. Rebellion rise up at UCLA? Was it a conscious, orchestrated move on the part of students or was it more organic?

It was more organic. UCLA had very few people of color in the 60s and 70s. I can name all the people of color who were in the film department when I was there. When Elyseo Taylor came to the film school in the 70s, he created the department of Ethno-Communications, and that brought in different groups of people of color. There was this notion that you were there to make films as a means for social change because we all shared in being part of a larger cause — the Civil Rights Movement. We met almost every evening to find a definition of what constitutes a Black film. We talked about what subjects we should tackle, who the writers and directors should be. There were some people, like Larry Clark, Alile Sharon Larkin, Chuck McNeill and Bernard Nicolas, who joined us.

What were the hot-button issues that propelled you?

The issues of the day: How people of color were treated, poverty, racism. Most of us came to the meetings as a reaction to all the negative films that Hollywood had made about people of color. We were reacting against those films, particularly Blaxploitation films. We didn’t feel those represented who we were and so we started to find our own definition of what a Black film was.

Your films were part of a tour in the 80s. Tell me about it.

[Author and film archivist] Pearl Bowser, [Philadelphia cultural officer] Oliver Franklin, and Cornelius and Linda Blackaby collected a body of Black independent films and put them on a tour throughout the country. We were invited to go and talk about these films in different places.

Killer of Sheep had success in Europe, didn’t it?

French journalist Catherine Ruelle, Berlin Film Festival programmer Ulrich Gregor and arthouse programmer Ard Hesselink put together a retrospective of Black independent film, which was shown in Paris, Berlin and Amsterdam. The European critics were looking for new trends in art; for innovative forms and different content. They featured our films in special screenings, and audiences and critics were just amazed by our work. We were the talk of the town, in all of the major papers and magazines. It felt like when jazz was first introduced to Europe and Black people went over there to find a better reception and treatment.

It wasn’t until I went to Europe, won the Critics’ Prize at the Berlin Film Festival and got funding from German Television ZDF and Channel 4 in England, that I realized that I could make an income making more films.

Your stories were reflective of the times in which you’ve lived.

I grew up in South Central. A lot of the kids I went to school with were never encouraged be something, though some became lawyers and principals. The kids I hung out with, however, didn't. They dropped out of school. Gangs were a big attraction. One of the things that may have helped me not get involved in gangs was that I had a very bad speech impediment. Because of that, I stayed back and looked at things rather than participate in them.

When I went to UCLA, I still lived in the community and hung out with my friends. What I noticed, during this time, was that I began thinking differently than they did because of the college education I was receiving. We argued about everything. I realized then that I couldn't speak for the community. I could only show it as it was. Killer of Sheep was an attempt to present a film that represented life there. I made it about people I grew up with and what happened to them and where they were at that particular point, trying to make sense out of it without imposing some sort of resolution. At the same time, I was impacted by neo-realism and their ideas of filmmaking.

What did your friends think of you becoming a filmmaker?

I didn’t tell people in my neighborhood that I was studying film until I did Killer of Sheep and brought my filmmaking there. I was trying to demystify filmmaking in the community. I wanted kids to see what making a film was like, to show them that they could do the same thing.

What is film’s purpose?

Film has to do something more than just make people laugh and escape. Film should shine a light on what connects us a people. Hollywood films have pointed out, in so many words, that they are not interested in making life fair or are deeply concerned about helping make life better for people in general. Don’t even mention people of color.

Hollywood says people aren’t interested in Black films or subject matter. When I was trying to get money for To Sleep with Anger, one of the companies that I applied to didn't want me to do the film because the content was too much about Black folklore. "The white folks in Indiana wouldn't be interested in watching a narrative that had a lot of story elements that are uniquely Black," they said, so I screened the film to a mixed audience in Indiana. The white people there were just as excited about the film as the Black people were. Everyone wanted to know why more films like To Sleep with Anger weren’t shown. I told them, "The people sitting behind me, my representatives, said that you folks wouldn’t understand it." They responded by saying that no one at the company asked them what they liked. I deliberately put the company on the spot. You have to struggle against false notions that have no foundation.

Whose work do you admire?

Spike Lee had a big impact in making young people interested in film; he developed a following as soon as he came on the scene. Third World cinema and filmmakers such as Ousmane Sembène; Oscar Micheaux was the first Black film director in the early days of filmmaking; Ossie Davis tried to make a film and so did Sidney Poitier and then Melvin Van Peebles; but they didn't have the appeal that Spike's films did. He moved the needle.

Have there been studio projects that you have turned down?

Yes. I had a chance to direct New Jack City (1991) but I turned it down. A studio wanted me to direct a film about Donald Goines, who wrote novels about gangster-like characters in the ghettos. His characters were intuitive; they had a second sense to escape and work in this environment. He may have been killed because he based some of his characters on real criminals in his stories. I was surprised by of the irony of it and I wanted to do a story about that aspect — a person who had all this wherewithal and knowing about those characters, becomes a victim of them. But the studio just wanted to show the Black community infested with drug addicts. I didn’t want to do that.

Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Posted: February 4, 2020