News

Real-World Knowledge

Festival Programmer and Publicity Consultant Kathleen McInnis helps artists become career tacticians

Kathleen McInnis teaches a Festival Strategies class at TFT that emphasizes the crucial importance of participating in relevant film festivals around the world, and teaches students how to put together effective entries that will get noticed by selection committees. The class is a prime example of TFT's commitment to helping talented students chart a creatively fulfilling course through the intricacies of the entertainment industry.

McInnis received her B.A. in Acting/Theater at the University of Washington. As a film festival strategist and publicity consultant specializing in world cinema, documentary and short films, McInnis represents films at the most respected film festivals in the world including Sundance, Toronto, Berlin, Cannes and Karlovy Vary. For six years, she was the director of publicity and promotion, and lead film programmer for the Seattle International Film Festival. At the same time, she worked as a film journalist for various publications including MovieMaker magazine. She left the festival to pursue freelance writing and independent producing but returned in 2001 to produce the fest’s annual Fly Filmmaking Challenge and one of its entries, director Guinevere Turner’s short film “Spare Me.” She was festival director for the Slamdance Film Festival in 2005 and is currently the film curator and director of industry programming at Palm Springs ShortFest. She has also provided expert unit publicity services for such films as “The Scoundrel’s Wife” (2002), “Hard Candy” (2005) and “Fido” (2006).

What power do festivals have — and how do you explain it to young filmmakers?

KATHLEEN MCINNIS: The simplest way to say it is that the festival circuit is like the farm system in baseball — an arena in which up-and-coming young players have a chance to show the scouts from the majors what they can do. Back in the day, making a movie for Roger Corman, or a little later, a music video, would have had a similar effect.

The first thing I always say in my classes is, ‘The film industry is built upon fear.’ Everybody wants to be first to be able to say they found somebody, but they don’t really want to be first. They want somebody else to have already validated their choice. Festivals and festival programmers have become that validation.

The influence of film festivals seems to have grown since the premiere of Steven Soderbergh’s “sex, lies and videotape” at the Sundance Film Festival in 1989.

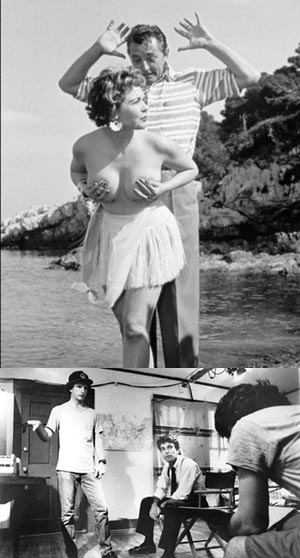

MCINNIS: Certainly the impact of festivals on American independent cinema has to be traced back to that year at Sundance. But if you really look at it, just one event decades earlier first put film festivals on the map. That was the starlet who took her top off in front of Robert Mitchum at Cannes in 1954. Everything changed at that moment, because those pictures landed on the front page of newspapers all over the world within a few hours. That one photo jump-started the media attention with regard to film festivals.

But while “sex, lies, & videotape” gave notice of the potential of independent filmmaking in America, it helped create the independent market, as we understand it today. That potential wasn’t realized right away because we didn’t yet have the platforms and the facilities for changing how people have access to films. I don’t think this all really came together, until as recently as five or six years ago.

To me, it was a film called “Four-Eyed Monsters,” which played at Slamdance in 2005, that started the shift in how festival films reach the public. It was well liked and well reviewed, but it wasn’t picked up for distribution. The filmmakers, Susan Buice and Arin Crumley, took matters into their own hands. They used every means available, from Video on Demand to online podcasts to BitTorrent download, to get their film out to the public, and in the process, they changed how people viewed what could happen with independent films.

What it is that you are teaching in the Festival Strategies class?MCINNIS: I would love to impart to students the concept of thinking about the end game from the very beginning — not to change your creative process but to help you at every stage, when you’re editing, when you’re in post, to think, ‘This is where I want it to go.’ I don’t want you to change how you creatively do what you do. I want you to be a better, smarter, faster thinker about how you do what you do.

I deconstruct the festival myth first: What is the festival here for? What does it do? There are certain festivals that can satisfy a long list of needs – industry attention, press coverage, awards, audience feedback. Then there are festivals that can only offer some of those things. Depending on the scale or the style of your film, it might get lost in the shuffle at one of the bigger festivals. Maybe one of the smaller or idiosyncratic festivals would be a better fit. One of the hardest things for filmmakers to have is that kind of self-knowledge about their work.

What are your goals and expectations for you want? How does that list match up to the festival list? How does your film match to both of those lists? I know what my goals and expectations are, I know which festivals will give me the best bang for my buck, but what kind of film did I make? Can that film support what my goals and expectations are, and is it the kind of film that can get programmed at that festival? The first two are easy; the third part of the triangle is very difficult.

I do feel a little bit like I’m on a mission to get this message out. I believe, firmly, that you cannot responsibly educate new filmmakers if you don’t teach them all the parts of the puzzle. It’s not enough to teach them how to operate a camera, write a script, or even how to think visually when telling their stories. Filmmakers are now responsible for doing the heavy lifting and being in charge of their own direction and determination. It’s a disservice to them to let them walk out of this system, which has supposedly trained them, ill prepared or completely unprepared to go out into the business.

Is that kind of thinking incompatible with being creative?

MCINNIS: That’s the fine line, the razor’s edge that I walk. It’s basically right- and left-brain thinking. I want students to venture across the great divide and think about these things and know about them, but I don’t want them to influence what they do creatively.

What are the ways around this? You can get a producer who will think this way for you. And also you can find a way to incorporate what you’re learning into your creative process and to be inspired by it. I want you to know what’s out there, what the zeitgeist is, what other people are doing. I want you to know what the game is, and to find your own individual way to incorporate that into your process.

— Posted Jan. 9, 2012; updated Jan. 22, 2014

Contact Us | Intranet | Internships | Careers | Privacy Policy | Sitemap | Media Relations

©2024 UCLA