News

In High Regard

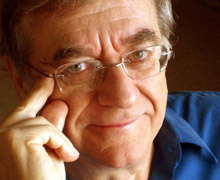

Professor Emeritus Howard Suber named a recipient of the 2014 Dickson Emeritus Professorship Award

By Noela Hueso

When UCLA Professor Emeritus Howard Suber was 16 years old and just named “Top Debater in the State of Michigan,” he boarded a Greyhound Bus in his hometown of Owosso, Mich., and headed for Cambridge, Mass., with an audacious plan: To walk into the admissions office at Harvard University, uninvited, and request to be interviewed for admission as a freshman.

It was a bold move, to be sure, but not a surprising one for those who know the witty and outspoken Professor Suber, who has been named one of two recipients of the prestigious 2013-2014 Dickson Emeriti Professorship Award, the highest honor bestowed upon a retired faculty member of the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Dickson Professorship, named after former UC Regent Edward A. Dickson, who served from 1913 to 1946, was first handed out in the 2006-07 academic year. It honors outstanding research, scholarly work, teaching and/or educational service performed by an emeritus/a professor since retirement. Like each of the UC campuses, UCLA received funds that will support one or more award each year. Suber is only the second professor from the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television (UCLA TFT) to win the Dickson, after Professor Vivian Sobchack’s recognition last year.

“Receiving the UCLA Dickson Emeritus Professorship Award is a great and distinctive honor and no one is more deserving than the remarkable Howard Suber,” says UCLA TFT Dean Teri Schwartz. “We are all so very proud of him and so fortunate to call him our colleague, professor and friend.”

Suber is modest about his merit.

“Previous Dickson winners have been people with international reputations, my counterpart included,” he says, referring to the UCLA School of Medicine’s Dr. Eric (Rick) Fonkalsrud of the Dept. of Surgery, a master surgeon and one of the founders of the specialty of pediatric surgery, who has also received a Dickson Professorship this year.

According to UCLA TFT Department of Film, Television and Digital Media Chair William McDonald, Suber’s self-effacement is characteristic.

“To meet this quite humble man, you would never know he had legions of devoted followers, but he does,” McDonald says. “I was one of those fortunate enough to be one of Professor Suber's students many years ago. He has one of the most brilliant minds I have encountered in my nearly 30 years as a university instructor and even today, I hear students rave about his teaching as students did in my generation.”

In his 49-year career at UCLA, he has always had the philosophy that if you want something to happen, you’ve got to make it happen. It was this attitude that allowed the former associate dean and 1989 recipient of the UCLA Distinguished Teaching Award to be instrumental in the creation of three key components of what is now the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television: UCLA’s Critical Media Studies and Ph.D. programs, the UCLA Film & Television Archive and the UCLA Producers Program, all of which he headed as well.

Over the passage of nearly half a century, Suber has taught 65 different courses, spanning all genres from documentaries to film comedy, and though he took early retirement 20 years ago, his illustrious career at UCLA is far from over. Since 1994, he has continued to teach two courses a year: “Film Structure,” on the power of film and narrative structure and either “Advanced Film Structure” or “Strategic Thinking in the Film and Television Industries or Is There Life After Film School?”

Professor Suber didn’t know when he walked into the admissions office at Harvard back in 1954 the path his life’s career would take but his unconventional plan to get into college worked: In his senior year, while many of his contemporaries were heading off to law school and medical school, he decided to pursue a graduate degree in film. In those days, “Nobody who wanted to get into film had any idea how that was done,” Suber recalls, “but I heard there were these two schools on the West Coast called UCLA and USC that had graduate programs.”

He chose UCLA. But he wanted to be a screenwriter and, like so many later students, was impatient to get out into the world. So, he left the program and was taken under the wing of an agent at MCA, at the time the entertainment industry’s biggest talent agency. Ultimately, nothing came from his relationship with MCA except frustration, although it did provide him with life lessons that he has incorporated into his UCLA classes.

Professor Suber returned to the master’s degree program at UCLA and, at the end of his first year back, he was asked by then-film department chair Colin Young to teach a course in American film history.

“I thought it would be a one-time gig. But one thing led to another however, and I discovered that I liked teaching,” he says.

After receiving his master’s degree, Suber was subsequently hired as a part-time lecturer and a couple years after that was told by the administration that if he got a Ph.D., he could have a tenured track position. UCLA didn’t have a Ph.D. program in film at the time — but there was one in theater history.

“This accounts for why 49 years later I still begin my ‘Film Structure’ class by talking about Oedipus Rex. I thought it would be good to use what I learned in my Ph.D. program somewhere,” Suber says with a wink.

Over the years, Suber didn’t let California state budget cuts stand in the way of creating and growing programs that continue to make an impact not only at the university but also around the world.

After Colin Young, who had begun the effort to create what is now the UCLA Film & Television Archive, exited the university to head the British National Film School in 1971, Suber was asked if he’d be willing to take over. At the time, there were no films, no budget and no staff.

“With all the budget cuts that were taking place in the early 1970s, there was no reason to suspect that the archive would get any money from the university, so I said, ‘of course, I’ll do it,’” says Suber, who dispensed with protocol and formalities and personally negotiated with studios, receiving about 2,000 prints, mostly from 20th Century Fox and Paramount.

“My theory had been if we build a valuable collection, the university would have to take care of it and if we had a valuable collection, we might then be able to raise private money to support it. It was true, of course, but I couldn't prove it at the time. We just had to do it and see how it would turn out.”

Today, the UCLA Film & Television Archive is the second largest archive in the United States, second only to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., funded by individuals, foundations, grants and the UC system itself.

Perhaps the toughest program to get off the ground was the Ph.D. in film, which Suber saw as a fitting addition to the school. He wrote a formal proposal for the creation of the program but it wasn’t until his eighth proposal was submitted that the Academic Senate faculty within the department and the outside jurisdictional committees and administration finally accepted it.

“Several faculty members inside the department feared that strengthening scholarly studies would ruin the film program,” Suber recalls, “while several outside faculty felt film wasn't scholarly enough to warrant a Ph.D. program.”

As things turned out, the concern was unnecessary. Today the UCLA TFT Ph.D. program in film, television and digital media is considered one of the finest in the world.

In 1987, Professor Suber became convinced that the university and its students would benefit from the creation of a Producer’s Program specifically in film and television and he agreed to chair such a program. As usual, there was no money to start a new program, so he met with heads of studios and other major players in Hollywood and asked them to teach in the fledgling program.

“If a luncheon with these folks went well, I would end by saying, ‘of course, you understand, we wouldn’t insult you with the kind of salaries the University of California pays…so there’s no money attached to this,” Suber chuckles. “So, the whole program was originally built out of free labor.”

Professor Suber took voluntary early retirement in 1994, but has continued to teach part time ever since. In 2006, Suber wrote “The Power of Film,” which looks at popular films such as “Casablanca,” “The Graduate” and “The Godfather” and examines why they continue to remain popular with present-day audiences.

In 2012, he published “Letters to Young Filmmakers: Creativity and Getting Your Films Made,” a compilation of advice he’s given to students through the years. Suber is currently writing his next book, “Sacred Dramas for a Secular Society,” which has the thesis that certain films serve the same purpose for secular audiences that religious stories serve for people of faith.

Suber doesn’t like to reveal the bold-faced names who have passed through his classes “because it suggests that I had something to do with their success,” he demurs. Nonetheless, in last quarter’s “Is There Life after Film School?” course, successful former students were the featured guests each week.

“Bringing in people who are thriving in the industry and who were sitting in this very same class as recently as a year or two ago speaks more than anything I personally could say that there is hope for them,” Suber says.

Judging from the amount of congratulatory emails that Suber has received in the wake of the Dickson Professorship award announcement on Thurs., May 1, it’s safe to say that Suber has, indeed made an impression on his students, both past and present.

Posted: May 1, 2014